PREVENTION OF TICK INFESTATION in PETS and HUMANS

Prevention of tick bite in humans

Prevention of tick bite in pets

Avoidance of pet exposure

Searching of pets

Topical treatments on pets

Systemic treatments for pets

Vaccines for pets

Bandicoot Management

Garden Management in the Pittwater area- by Bill Conroy

Observations on the incidence of ticks in relation

to native flora and native bird life- by Claire DeLacey

Footnotes

About DEET

About permethrin toxicity in cats

Summary of commercial products aiding in the control

of tick paralysis

Some links on on tick control products

Prevention of tick bite in humans (TAGS recommendations, 2000)

Ticks occur in moist sheltered bushy areas and gardens. They may drop on clothing as you brush against shrubbery, or drop from overhanging branches. Ticks like weedy areas, especially Lantana.

Dress appropriately for bushwalks or gardening. Wear a wide-brimmed or floppy hat, long-sleeved shirt, and long trousers tucked into socls. Ticks are more easily seen on light coloured clothing.

Spray clothes and hat with with insect repellant brands containing pyrethrum/pyrethroids, prefereably the night before wearing. Pay attention to openings e.g. collar, cuffs, fly and hang on a coathanger to dry OR treat clothing with permethrin which will endure up to 7 washings. Also use insect repellant with DEET on exposed skin [most common insect repellants contain DEET].

Check clothing and pets before entering the house. Remove clothing to check family for ticks. Pay attention to head, behind ears, groin, armpits and back of knees. For those people who may be exposed to ticks in the backyard, it is a good idea to use a set of "outdoor" clothes which can be promptly removed (and ideally washed in hot water) once inside the house.

Be careful where you put the clothing e.g. it may introduce ticks into your bedroom, carpeted areas, sofas etc.

Mow the grass and keep the garden neat. Trim shrubs overhanging paths. Ticks like damp, moist areas such as woodpiles and mulch. Spray vegetation with permethrin (a synthetic long-acting form of the naturally occuring pyrethrum).

[The best means of tick prevention is to avoid the areas where they are. If you can, walk or ride on the wider tracks and avoid brushing the vegetation along the edges. Because animals often traverse the edges of clearings, these tend to be hot tick spots.]

[TAGS is Tick Alert Group Support PO Box 95, Mona Vale, NSW 1660. Medical Advisor: Dr B. Hudson, Microbiology, Royal North Shore Hospital Scientific Advisors: Bill Conroy, Sydney; Dr Michelle Wills, PhD Newcastle. TAGS is a self-funded non-profit organisation.]

Prevention of tick bite in pets

Avoidance of pet exposure

The paralysis tick is generally found in coastal regions of NSW and Qld. This generally means East of the Great Dividing Range, generally within 50 km of the coastline. See also Distribution.

Ticks require warm (not hot; ideally 7-32 C) and humid weather. They also require an appropriate range and density of fauna to act as intermediate and end stage hosts. Avoiding areas that may be traversed by native mammals is the simplest means of prevention. Unfortunately, backyards adjoining natural bushland are at risk of intrusion by native marsupials.

Clipping. Keeping a dogs coat clipped short (just 2-3 cm) makes finding ticks easier. This is particularly so for dogs predisposed to matting of the coat. Clipping a coat too short may increase the risk of sunburn however.

Searching pets

Daily examination remains the least expensive and most effective form of prophylaxis, as the disease will not develop until ticks have been attached for at least 4 days. Searching may need to be continued for a week or more (perhaps longer in cool weather) after a dog has been exposed to the risk of picking up ticks. A combination of inspection and palpation (feeling) is best. Most ticks will be found on head, neck and shoulder regions. Ticks can be mistaken for nipples or superficial skin tumours if one relies on palpation alone. Some ticks are in a prominent position such as on the nose or eyelid but may be missed because they are hidden by matted hair or resemble warty skin tumours. One needs to remember that tick paralysis may still develop 24-48 hrs after a tick has been removed. See also Removal of ticks.

Topical Agents on pets

Follow manufacturers directions carefully! No chemicals can be relied upon entirely to prevent tick paralysis. The following gives a more general discussion about some of the products available. For a tabulated summary of the commonly used products go to A summary of tick prophylaxis products.

Sprays and Rinsesfipronil

The insecticidal spray fipronil (Frontline® Spray) when applied as directed once at maximal dosage (6 mL/kg) is claimed to control ticks for up to 3 weeks. The spray is sold as 100 mL or 250 mL spray bottles. It is safe on cats older than 7 weeks and puppies older then 2 days. Fipronil is not a repellant. It kills fleas and ticks when their cuticle comes into contact with treated skin and hairs. Ticks that are already attached on an animal may, however, require a variable period to be killed (up to 24-48 hours after application)- therefore fipronil is probably not the best acaricide when pre-killing ticks prior to removal- household insecticidal sprays are probably more reliably rapid (Elizabeth Court pers. com.). Daily searching is still recommended. Further information about fipronil (Frontline) is available from the manufacturer Merial, or Rhone-Poulenc (toll free line is 1800 808 691). Fipronil is also used as an agricultural pesticide.

permethrin

The insecticidal spray/rinse permethrin (Permoxin®) is claimed to be able to repel ticks when used weekly as a rinse. When a dog is going into a known paralysis tick area it should be used as a spray (or rinse) just before entering that area and again when leaving that area or arriving home. Daily searching is still recommended when ticks are active. It is registered for use in dogs. It is less expensive than Frontline Spray. The manufacturer (Dermcare-Vet Pty Ltd) claims that the active ingredient causes paralysis of the tick's mouthparts and therefore prevents further toxin excretion, and for this reason recommends applying Permoxin to dogs when attached ticks are found. Permoxin is claimed to be effective where a dog is washed with shampoos frequently because it binds to hair rather than lipids (cf whilst Frontline® resists plain water bathing, it is perhaps less resistant to shampoo bathing). When diluted in water Permoxin remains stable for 2 months, and when diluted in methylated spirit it remains stable for 1 year+.

"The independent University tests to NRA protocols of Permoxin® are published in the AVJ (1994) for paralysis ticks and fleas. Despite a 100% efficacy up to 14 days and a 97.6% tick efficacy at 21 days, Dermcare chose to go with the conservative claim of recommending weekly rinsing. In reality no prodcut is 100% effective as there are too many variables in home based treatments. Thus daily searches are important. I like to recommend that apart from these routine measures, when walking the dog in tick areas a top-up spray with Permxiin before or after the walk is an added precaution." - Dr Ken Mason (Veterinary Specialist Dermatologist) Tick Paralysis: Snippets and Opinion. Dermcare-Vet Derm News Vol 3, Issue 1, Spring 2000.

Clinical use of Permoxin as per article by Kenneth Mason BSc MVSc FACVSc (ANIMAL ALLERGY AND DERMATOLOGY SERVICE): The treatment of a paralysed dog to reduce the incidence of toxin secretion upon tick removal: A personal viewpoint based on previous experience.

- We paint the ticks (cotton bud into 10mL chamber of

Permoxin concentrate) to block toxin secretion, then remove

the tick before the animal is put into a cage (usually after being given antitoxin

and an antacid, like ranitidine injection).

We expect the tick to be dead from permethrin paralysis in a few hours but toxin secretion blocked immediately.

If you spray with diluted Permoxin or shampoo and then follow with Permoxin diluted rinse, I expect the tick to die over the next 24hrs (a lot slower).

We have experienced live ticks, the next day under a mat of hair and on the face. We suspect a lack of Permoxin penetration or reluctance to put the rinse on the face by the operator to explain these occurrences. We shampoo first in pyrethrum shampoo to enhance the Permoxin2 rinse penetration. - There has been a push lately, to show that products

causing salivation and excitation before killing ticks have not shown increased

evidence in anaphylaxis, thus it is argued there is no need to use a tick

product to prevent toxin secretion.

The original human reports were that occasional removal of live ticks was followed by anaphylaxis in the absence of tick antisera. This observation implied a release of toxin/saliva at removal and thus the need for a pyrethroid first. The second issue that pulling off live ticks or spraying with an insecticide (causing toxin release) might be a reason for the sudden unexplained deterioration in paralysis of some dogs within 24 hrs of tick removal. This issue has not been addressed. This is the principal reason for continuing to paint ticks with a pyrethroid before removal, some vets freeze 3 the ticks in situ for similar reasons. The tick can be removed any time later ie-after 10 minutes, if it is paralysed by Permethrin or frozen in situ

coumaphos

Organophosphates: Coumaphos (Asuntol®)- weekly bathing has been shown to prevent attachment of Ixodes holocyclus for one week; it is a chemical which is potentially toxic to animals and operators; it is not used for cats, or for sick, aged or young animals.

"Spot" treatmentsfipronil

Frontline Top Spot® for dogs is claimed to repel paralysis ticks for up to 2 weeks and Brown dog ticks (Rhipicephalus sanguineus) for up to 4 weeks. Top Spot perhaps should not be relied upon to actually kill attached paralysis ticks (Geoff Turnbull, pers com.). The Top Spot home page states: "Fipronil localizes in the hair follicle and continues to replenish itself on the pet's skin and hair, thus remaining effective even after bathing. Safety studies have also confirmed that Frontline® Top Spot™ is gentle enough for use on 10-week old puppies and 12-week-old kittens, as well as pets receiving other medications." [It is not clear what is meant here by "other medications"- whether Frontline is compatible with other insecticides for example.] The chemical is claimed to quickly (within 24 hours) move through the oils of the skin covering the dog and then collect naturally in the hair follicles and oil producing glands of the skin, which thereby act as a reservoir that continually reapplies the insecticide to the hair. The product is a small squeezable vial of liquid that is applied directly onto the skin between the shoulder blades of the dog. Because of the strong grooming habits of cats, topical spot tick repellants cannot be marketed as being a reliable protection against tick paralysis. For high risk areas it may be advisable to combine Frontline Top Spot with Frontline spray, the spray being concurrently applied to the head/neck/shoulder/chest/foreleg region of dogs (Elizabeth Court pers. com.).

permethrin

Exetick® (Schering-Plough) is another spot-type topical flea and tick preventative, apparently also spread in the skin's lipid layer. It is not intended for use in cats. Claimed to repel and kill ticks for up to 2 weeks (fleas up to 4 weeks). Spreads over the coat in 6 hours in small dogs and 24 hours in larger dogs.One tube for small dogs and 2 for large dogs. Safe on pregnant and lactating bitches and can be combined with other animal treatments including heartworm control. Dogs can be shampooed before applying Exetick® but should be dried first. Occasional swimming is ok. Sold in wallet packs of 6 x 1mL tubes. Active ingredient is permethrin. Is toxic to cats. Made by Schering-Plough Animal Health Ltd ACN 000489 172, 71 Epping Road, North Ryde NSW 2113. SPV0012/CJB S0269.

Collarsamitraz

A collar impregnated with amitraz (Preventic®, Virbac) is claimed to offer 2 months protection- kills ticks within a few days after; application; however, after washing or swimming, it may take 24 hours for protection to be re-established and daily searching is still recommended.

propoxur

A collar impregnated with the carbamate propoxur (Bay-O-Pet Flea Collar for Cats®, Bayer Aust) is claimed to discourage tick attachment on cats.

flumethrin

Bay-O-Pet Kiltix® (Bayer, Aust) is a flumethrin-impregnated collar manufactured by Bayer. Flumethrin, a synthetic pyrethroid, is claimed to control brown dog ticks and bush ticks for up to 5 mths and aid in the control of paralysis ticks for 6 weeks. Daily checks are still recommended. The flumethrin is released from the collar as a fine powder which migrates through the dog's coat at skin level. The natural movement of the dog helps to distribute the active ingredients quickly. If the collar were inadvertently ingested by the pet the plastic matrix would not release enough active ingredient to be harmful to the pet. For most dogs an effective distribution of the flumethrin would occur within 24 hours. In dogs with very thick double coats it may take longer than this. The collar resists the effect of water. However it is recommended that the collar be removed during swimming and bathing as frequent wetting will remove insecticide from the coat and may shorten the life of the collar. The Kiltix® product brochure claims that this flumethrin collar is more efficacious than amitraz collars. Customer information line 1800 678 368 9 am-4 pm Mon-Fri.

Systemic Agentscythioate

The regular oral administration of the organophosphate insecticide cythioate (ProbanTM, 3mg/kg every 2 days; for 30 mg tablets- 1 tablet per 10 kg body weight; liquid 15 mg/ml, 1mL per 5 kg every 2 days) can be used to prevent tick paralysis in dogs, because parasites receive a lethal dose of anticholinesterase when they begin to engorge. This may be the treatment of choice in long-haired animals, especially those belonging to old, infirm or unreliably attentive owners. The animal must be accurately weighed before starting treatment. Always round the dose up to the next half tablet (e.g. 21 kg = 2 ½ tablets). The dose should be given every 48 hours- that is, one should develop a routine of giving the dose at the same time every second day. According to the manufacturer, Proban can be administered year round. Proban should not be given to any animal which is sick, pregnant, lactating, recovering from surgery, under 4 months old, or being treated with any other anti-cholinesterase insecticide. Proban is safe to use in conjunction with ProgramTM and SentinelTM (Novartis), FrontlineTM (Merial), AdvantageTM (Bayer) and all pyrethrin based products. Dogs travelling into tick areas should receive Proban one week before, during, and one week after their stay in the tick area. For flea control on dogs the same dose is used but it is only given twice weekly instead of every 48 hours. In a small number of cases, Proban may not be well tolerated. For these animals, alternative treatments are needed.

Proban is not marketed for tick control in cats. In areas with high tick risk a dose of is one quarter tablet (7.5 mg) per 5 kg every second or third day has been used but this is an extra-label regime, not officially endorsed. For flea control on cats ¼ tablet twice weekly or 0.1 mL/kg body weight is used.

[There have been reports of elevated liver enzymes with long

term administration of cythioate. These levels apparently fall

upon discontinuation. Nevertheless one would advise caution using

cythioate in animals with questionable liver function. It may be

wise to screen animals for hepatopathy periodically if on long

term treatment. See Proban- scientific

information for even more details.

Another point concerning long term use is efficacy. It is theoretically

possible for hepatic enzyme induction to gradually increase with

prolonged administration and so increase the rate of the

clearance of the drug. This may result in a gradual reduction in

efficacy. Alternating with other methods of tick control may

provide the answer to both potential toxicity and to loss of

efficacy of this product].

Ivermectin

(Ivomec®, Heartguard®). Not yet evaluated in dogs or cats but known to be acaricidal in other species. Apparently, may not be a reliable means of killing attached ticks in dogs (Elizabeth Court pers.com.).

Milbemycin

Similarly milbemycin (Endovet®) has not been evaluated but it also is effective against mites at high doses.

Moxidectin

There has been a report of Cydectin Pour On® (moxidectin 5 g/L) being used to control ticks in cats at a dose of 1000 mcg/kg body weight (see Fort Dodge Aust, Pty Ltd, ACN 000 074 702 PO Box 234 Baulkham Hills NSW 2153, 23 Victoria Ave, Castle Hill, NSW 2154, tel 61 2 9899 2111, fax 61 2 9899 2151). This use is off label at this stage.

Vaccines for pets

The following information about vaccines comes from news releases:

"Paralysis tick vaccine marketed

within five years", An article in The Veterinarian:

July 1995, by Jane Kahler.

"Better weapons are on the way",

An article in Australia's Dangerous Creatures, Readers Digest,

1991.

"Vaccine gives tick the flick",

An Article in The Australian, Feb 1998 by Madeleine Coorey.

"Tick vaccine trials on the way",

An article in The Veterinarian March 1998.

"Keep an eye out for any ticks",

An Article in the Illawarra Mercury, Oct 2000

Unfortunately, despite initial hopes, a successful vaccine may still be some years away (based on latest information I have received in 1999, see Current Research).

An article in The Veterinarian: July 1995: by Jane Kahler -

"Paralysis tick vaccine marketed within five years"by JANE KAHLER A paralysis tick vaccine should be available within five years as a result of Australian research aimed at producing therapeutic agents from snakes and ticks. Research led by Associate Professor Kevin Broady at the Department of Cell and Molecular Biology at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) is investigating the structure and function of neurotoxins of the Australian paralysis tick, Ixodes holocyclus. The team has also begun a project to isolate those proteins in the blood of Australian snakes which inhibit the neurotoxins in snake venom. I. holocyclus causes more than 80,000 cases of tick toxicosis in animals along Australia's east coast each year, killing thousands. The toxin, contained in the tick's saliva, is of a presynaptic type and so slow acting it has sometimes been demonstrated to take effect even after the tick has been removed. The longer the tick feeds, the greater the output of saliva (and of the toxin it contains), and the greater is the likelihood of fatality. Speaking at the recent Horizons of Science Forum organised by the Centre for Science Communication at UTS, Dr Broady said his work aimed to develop a vaccine against I. holocyclus by first isolating the gene encoding the tick protein neurotoxin so that large amounts of toxin could be harvested. To produce a vaccine, the protein neurotoxin would then be modified to reduce its toxicity without affecting its immunogenicity. Using similar techniques, Dr Broady's research has already identified proteins from the blood of snakes that inhibit the presynaptic neurotoxins which have phospholipase A2 (PLA2) activity, a major component of most snake venoms. Dr Broady said these proteins inhibited PLA2 activity in the venom of snakes from a wide range of origins. Based on this finding his team plans to develop a "universal" snake antitoxin. But because PLA2 was also central to inflammatory processes, Dr Broady said he believed these PLA2 inhibitors could also be modified to provide a treatment for human inflammatory diseases such as arthritis and asthma." |

An article in Australia's

Dangerous Creatures, Readers Digest, 1991 -

"Better weapons are on the way""The war against tick paralysis is being waged in Brisbane laboratories. Antitoxin to overcome tick paralysis has been made since the 1940s from serum taken from dogs. Foxhounds are conditioned to withstand heavier and heavier infestations of ticks - up to 200 at a time. It is a long process that produces good results, at a high price. on afflicted pets. But the antitoxin is used reluctantly on humans. in only the gravest of cases. Substantial quantities have to be injected, and too many people have a severe allergic reaction to protein originating in dogs. Brisbane staff of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation have succeeded in producing a more potent serum more quickly in rabbits. and in modifying it so that it promotes immunity without any toxic effects. They are on the way to making not only an improved antitoxin for paralysis victims, but also a vaccine that could be given to pets and livestock and to humans at special risk. A better way of desensitising allergy suff'erers, using an extract from tick salivary glands instead of now- abandoned whole-body extracts. is also in prospect. The last major step is to develop a method of mass-production. This calls for the breaking down and separate identification of all the components of the toxin protein. Then techniques of genetic engineering should be able to do the rest. Researchers are confident of achieving their aims in the l990s." |

An Article in The Australian, Feb 1998 -

"Vaccine gives tick the flick"by MADELEINE COOREY. IT begins with nausea, a wobbly feeling in the legs and constricted breathing. It ends in paralysis and death. But a world-first vaccine designed to prevent a problem that hits about 80,000 pets annuallyis set to break this cycle. Researchers at the University of Technology, Sydney are about to begin clinical tests of a groundbreaking serum to immunise dogs, cats and other farm animals against the ravages of the paralysis tick. There is a growing incidence of the tick in cattle, horses, alpacas and deer, according to the head of UTS's department of cellular and molecular biology, Kevin Broady, who has secured an international patent for the method of developing the vaccine. The mostly deadly tick in the world, the paralysis tick, is found along Australia's east coast. Conventional treatment involves removing the tick, adinistering an antivenom and hospitalising the animal for two or three days, at a cost to the owner of between $220 qnd $300. While animals can be successfully immunnised against cattle tick, which is prevalent in Queensland, until now there has been no vaccine available for the paralysis species. Associate Professor Broady said there was the potential for the vaccine to be modified to be used against the South Afrocan "spring lamb fever tick" and the North American "lone star tick". "Up until a few years agoI would have thought it was an Australian market only... but if you can show there's a similar toxin there we can do a similar thing to what we are doing here and there would be a larger market" he said. Professor Broady said UTS researches identified part of the structure of the neurotoxin ticks inject into their prey several years ago and from that they were able to isolate the gene responsible for the posion and produce a synthetic version. Production of a commercial vaccine cannot commence until scientists can produce large amounts of the toxin. It would require millions of ticks to get enough poison naturallyto treat only a few animals, Professor Broady said. Professor Broady said the researchers would continue their work on the effects of ticks on humans, including a search for a cure for people allergic to ticks. Veterinarian Greg Ross, wo supplied Professor Broady with ticks for research, said the vaccine was a fantastic development. "It's just going to alleviate so much suffering from animals that are affected", Dr Ross said. |

An article in The Veterinarian March 1998 -

"Tick vaccine trials on the way"Researchers at the University of Technology, Sydney (UTS) have produced the world's first tick toxin vaccine, which could save tens of thousands of Australian domestic dogs and farm animals. UTS and its commercial partner, Novogen (formerly Norvet), are stockpiling the vaccine and will begin trials on dogs in December. They hope that by the end of 1999 an improved antitick serum will become available, and by the end of 2000 the vaccine will be on the market. Cell and molecular biology department head Associate

Professor Kevin Broady said the vaccine would make full

immunisation against tick paralysis possible and reduce

the cost of treating affected dogs. "Current treatment involves administering an immune dog serum, a costly procedure that causes complications when given to animals other than dogs", he said. More than 80,000 cases of paralysis tick toxicosis, mainly in domestic cats and dogs - are treated each year in eastern Australia. The most heavily infested area is around Lismore, on the NSW north coast, where the paralysis tick has spread through cattle and deer farms as well as infecting newly introduced livestock species such as alpacas. Previous efforts to manufacture a vaccine have been frustrated by the tiny amount of venom produced by each tick. However the UTS work progressed rapidly after The Veterinarian reported in July 1996 that the researchers had isolated the gene responsible for the neurotoxin. Gene splicing and recombinant DNA technology was used to produce the venom in sufficient quantities to use as a vaccine. |

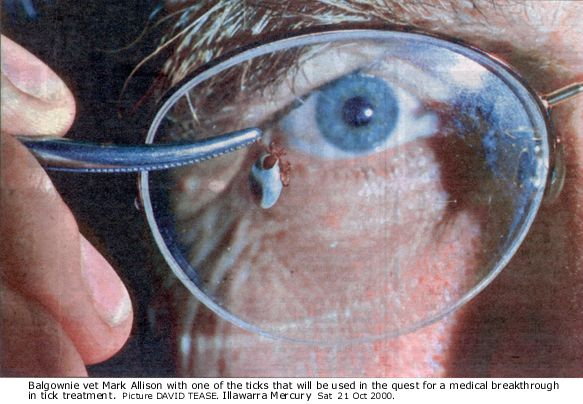

An article in the Illwarra Mercury 21 Oct 2000

"Keep an eye out for any ticks"By Michele Tydd The despised tick is now a wanted species in the battle to advance canine and feline wellbeing. Balgownie vet Mark Allison is calling for pet owners to support a research program by handing over ticks found on animals. "A tick can kill a dog or cat in 3 days and at last scientists are close to a vaccine to serve as protection, in the form of an annual vaccination," Dr Allison said.

A team of researchers at the University of Technology, Sydney took eight years to find enough toxin ticks to extract the toxin for DNA duplications to make a synthetic poison for a vaccine. Dr Allison said the first batch was tested recently but didnt work because the shape of the DNA was not perfect. He said vet clinics throughout the Illawarra had been asked to save all the ticks they could for collection in January for the second batch of vaccine. "As a tick only holds one-hundredth of a drop of poison we also need help from the public," he said. "It's a worthwhile project because although ticks are only as big as a pea they can cause real suffering by paralysingthe animal and eventually causing heart failure". Ticks can be placed in jar and dropped off to any vet in the Illawarra. "This is an excellent way to make a real contribution to medical breakthrough," Dr Allison said. |

See also Toxicology

Garden Management

The following information is extracted in part from "Bandicoots, A disappearing part of Sydney's environment, produced as a combined effort by NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service and Pittwater Council, June 1995; NPWS 43 Bridge St Hurstville 2220 tel 02 95856333; Pittwater Council 11/5 Vuko Place, Warriewood 2102 tel 02 99707222).

Bandicoot ManagementA yard close to bushland can be made less attractive to tick hosts such as bandicoots. Regular garden maintenance by controlling tall grasses and weeds helps. Removing leaf litter and controlling snails and slugs should also help. Wear gloves, long sleeves, long pants and use a high grade insect repellant when performing such yard maintenance. Removing the noxious weed lantana (Lantana camara), which seems to be a favourite site for ticks and their hosts, is also useful. It is possible to live side by side with the native wildlife that visits our gardens. The native animals that may, from time to time call your garden a sanctuary, can be accomodated in purpose-designed areas. Establish a separate area in the garden which provides shelter and food for native birds and animals while your family and pets can use a more formal, manicured area. Your native animal animal habitat area should be located so it is not a major family or pet thoroughfare. Then, if ticks are present, they are less likely to attach themselves to passing people or pets. An alternative is to construct bandicoot-proof fencing around the yard. Use fine galvanised wire mesh or any other material with gaps no larger than approximately 20 mm. The foot of the mesh should be buried at least 150 mm and it should rise at least 500 mm above the ground. Garden PesticidesWhilst a yard may be sprayed with malathion or pyrethrin products the effect is usually short lived and many normal and desirable insects and arachnids will be destroyed [some of which may actually be predators of tick stages]. A "natural" alternative to chemical sprays is a mixture of chilli (cayenne powder), garlic and vinegar. After being left to brew for a few days, the mixture, sprayed around the garden , will discourage most pests. Please remember, it is illegal to trap or kill bandicoots unless authorised by NPWS. |

The following is an article by Bill Conroy:

The follwing article by Claire deLacey

Taken from a letter addressed to Tick Alert Group Support (TAGS), June 2001. With author's permission. Title created by Web author.

Observations on the Prevalence of paralysis ticks (Ixodes spp) in relation to native flora and native bird life.by Claire deLacey6th June, 2001 Having subscribed to TAGS and read the magazine articles with great interest, I'd like to take the opportunity to contribute my observations on tick distribution to TAGS. As a free-lance field botanist I work in a range of areas in NSW, from Jervis Bay in the south to Karuah in the north and Lithgow to the west. I have been interested in tick distribution for some time, as ticks are a considerable problem in my work. I have always been particularly susceptible to tick bites and find that I have experienced increasing levels of irritation and side-effects in more recent years. I live in Maianbar (near Bundeena in Royal National Park), where we have been inundated with ticks over the spring and summer months, though I'm happy to report that their numbers have declined steadily with the onset of colder weather. However, I have noticed an interesting increase in ticks in this area over the last few years. The general consensus in the neighbourhood seems to be that the success of the fox baiting programme in Royal National Park has led to an increase in Bandicoot numbers turning up in people's back yards, which has contributed to increased tick numbers. I have found the increase in tick numbers to be an interesting situation, but I'm not convinced that an increase in Bandicoot numbers is the complete picture. In areas surrounding Maianbar and Bundeena (i.e. in the Royal National Park) high numbers of ticks do not seem to be solely associated with good Bandicoot populations. I have suspected for some time that the increase in tick numbers is also associated with the fragentation of understorey vegetation in the area, with a consequent loss of habitat for small bird species. It may be that a loss of smaller bird species, which could play an important part in reducing tick numbers, would lead to an increase in tick infestation. Maianbar and Bundeena are small villages located at the mouth of the Hacking Estuary. Although much of the tree canopy has been retained (more so in Maianbar than in neighbouring Bundeena), most of the understorey which provides suitable habitat for small bird species has been removed or replaced with ornamental native, exotic or mesic (softer rainforest-type) shrub species. Additionally, the remaining sclerophyllous (heathy) vegetation remains unburnt (as in most suburban situations), and as most of the sclerophyllous plants need fire to promote regrowth and regeneration, they become displaced by mesic plant species. In addition, mesic plants are often better adapted to altered hydrological and environmental factors which follow on from increased run-off and nutrient levels common to suburban environments. Mesic species such as Sweet Pittosporum Pittosporum undulatum, which belongs naturally to the landscape, and weed species such as Privets Ligustrum spp. generally have a greater requirement for nutrients and water and create more humid environments than do their heathy counterparts. Stands of mesic species also create a dense canopy beneath which heathy plants cannot regenerate, thereby removing habitat for small birds. These humid environments tend to make very suitable habitats for ticks. When I spend time in my garden I am aware of the plant species which are likely to be host to ticks. They seem to turn up most commonly on exotic species such as Mulberry Morus alba, Banana Musa spp. and in unmown grass. They also occur on ornamental native species such as Lillypilly Acmena smithii, Magenta Lillypilly Syzygium paniculatum and often isolated specimens of Eucalyptus species. In a single visit to the areas of my garden where this vegetation is concentrated I can sometimes be the target of 30 or 40 tick nyphs. Conversely, I can walk through areas of the Royal National Park just 10 minutes away from my back yard and bring only one or two adult ticks home with me. The vegetation in the villages of Bundeena and Maianbar (isolated large trees with little understorey) supports larger opportunistic native bird species such as Magpies, Currawongs, Cockatoos, Lorikeets, Ravens, Rosellas and Wattle Birds, and exotic species such as Indian Miners. These larger birds are further attracted into the area by being fed by local residents. Smaller native bird species numbers are declining, especially species like Silvereyes, Treecreepers, Gerygones and Thornbills, which normally feed on the ticks. It seems to me that the increase in the spread of urban areas, the removal of habitat and the alteration of the cycles of natural phenomena such as fire frequency all contribute to a variety of ecosystem responses, of which increasing levels of tick infestation is one. Unfortunately, attracting small birds into the garden might not be as straightforward as it appears; some of my own thoughts on this are as follows:-

None of the above constitutes proper scientific research; it is simply based on my own observations and hypothesising, and it is likely that research has already been done on this subject. If this is so, perhaps this information could be shared; then we might be able to do a little more to reverse biodiversity decline and rid ourselves of some tick problems at the same time. Claire deLacey |

Some animal tick repellant manufacturers

Permoxin®- Dermcare-Vet Pty Ltd ACN 010 280 010, Springwood,

4127, Australia, tel 07 3808 4761 FAX 07 3803 7967

Frontline®- Merial Australia Pty Ltd ACN 071 187 285 261,

Tingira St, Pinkenba, QLD 4008

Proban®- Boehringer Ingelheim Pty Ltd ACN 000 452 308, Animal

Health Division, 50 Broughton Rd, Artarmon NSW 2064- information

1800 226315 or 029482 4011.

Footnotes

About DEET

| DEET As a skin repellent DEET is apparently

the most effective topical insect repellent for humans.

It's chemical name is N, N-diethyl-m-toluamide. "DEET"

repels a variety of mosquitoes, chiggers (larval mites of

the genus Trombicula), ticks, fleas and biting flies; no

topical repellent is effective against stinging insects

such as bees and wasps. The US Armed Forces have long

used 75% DEET in ethanol, but several products that equal

or exceed this concentration are now available

commercially and all share the side effects of increased

toxicity. Ultrathon contains only 35% DEET (so it is also

safe in children). Other repellents effective against

both mosquitoes and ticks, but less so than DEET, include

2-ethyl-1,3-hexanediol (Rutgers 612) and dimethyl

phythalate. Citronella-based repellents (Natrapel; and

others) may provide short term protection against

mosquitoes, but are probably not effective against ticks.

|

About permethrin toxicity in cats

| Permethrin Permethrin in cats: warning

against use of some permethrin products in cats (letter) |

Some Links on Tick Control Products

For general tick control ( in the USA) see http://www.pestproducts.com/ticks2.htm

For info on potential pesticide toxicities (relating to organophosphates) see http://www.simplesteps.org/health/pets/toxic-flea-and-tick-treatments

The Paralysis Tick of Australia - Home

E-mail Us to report a broken link!